On Wednesday, August 13, B’nai Vail Congregation in partnership with Vail Symposium presented “Violins of Hope” to a sold-out crowd at Vilar Performing Arts Center at Beaver Creek. For more than 500 people in the auditorium and for many more watching online, this was a chance to hear violins from a collection that survived the death, destruction, and displacement of the Holocaust. Now privately owned, these instruments brought hope to a new audience in Vail thanks to the efforts of multiple people dedicated to the preservation of history through the voices of violins.

The Luthier

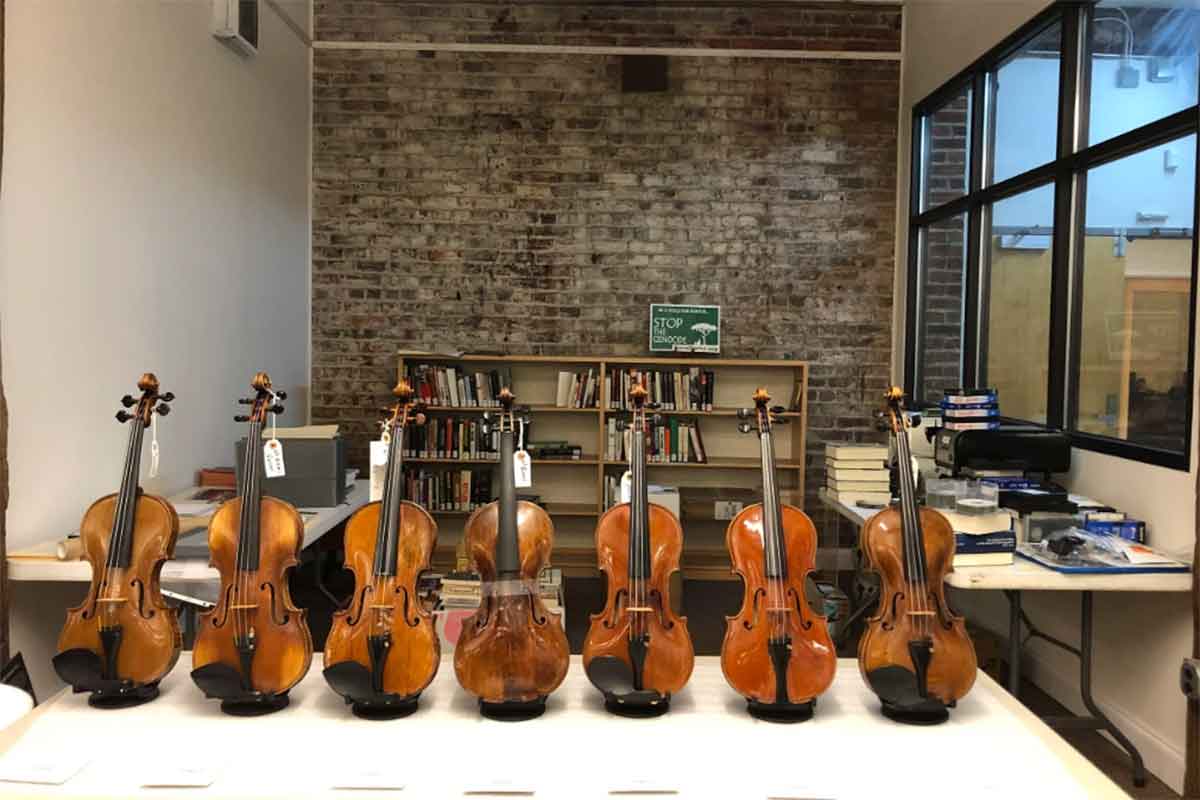

On the evening of the performance, Avshalom (Avshi) Weinstein, a third-generation luthier, strode onto the stage to introduce eight violins saved from destruction during and after the Holocaust. On this night, Avshi and his forefathers, who make, repair, and maintain stringed instruments, were in the spotlight, but the violins were the stars of the show.

Avshi’s grandfather emigrated from Poland to Israel in 1938 and opened a violin workshop. When Jewish musicians were banned from performing in Europe and fled to Israel to escape Nazi persecution, they formed what was then called the Palestine Symphony Orchestra and is now the Israel Philharmonic. They brought Avshi’s grandfather their German-made instruments because they did not want to perform on anything connected to Germany. His grandfather bought them, creating what Avshi calls a “beautiful, worthless collection.”

The collection remained quietly within the family until 1991 when a German apprentice to Avshi’s father, Amnon, persuaded Amnon to give a lecture in Germany about the violins. Amnon also spoke on a radio show in Israel, reaching out to people who owned instruments dating back to the Holocaust. By 9:00 the next morning, he started hearing from people who brought him family legacy violins.

The collection now includes more than 100 instruments, lovingly restored by the Weinstein family of luthiers. Avshi shared the stories of the violins that were used at the Vail performance, including the “Violette Silberstein violin.”

“In La Havre, France, where she grew up, Violette’s mother encouraged her to learn violin, but she was just an average player,” Avshi said. “When she was sent to Auschwitz, she auditioned for the women’s orchestra and was not accepted. But when a new conductor arrived—Alma Rosé, Gustav Mahler’s niece and a renowned musician—Violette tried again, and Alma Rosé accepted her. When Violette became too sick to perform and the SS wanted to shoot her, Alma Rosé stepped in and told them, ‘You cannot kill her. She is my best violinist!’

“Playing the violin saved Violette’s life at Auschwitz,” Avshi continued. “Years later, after her death, her two children handed her violin over to Violins of Hope. We opened the case, dusted it off, and that same evening, my wife performed on the violin with strings dating back to 1940. She played the same number by Jules Massenet that Violette had played to audition for the orchestra at Auschwitz.”

“This violin saved one life,” Avshi said. “Now it has come to Vail, Colorado, to again speak the truth so that all within earshot will never forget.”

The Rabbi

Rabbi Joel Newman of B’nai Vail Congregation likes to plan programs far in advance. Last year, he heard about a violin saved from the Holocaust that is on display in an Alabama museum, and he had an idea. What if we could bring that violin to Vail and have it played at a service?

The Birmingham violin turned out to be just the start of a much more elaborate plan. Rabbi Newman’s research led him to Violins of Hope and to Avshi Weinstein. The idea of one violin traveling from Alabama to services at B’nai Vail was transformed into eight violins traveling internationally for an interfaith community performance with Vail Symposium.

“I have done things like this before with remnants of the Holocaust,” Rabbi Newman says. “This is very similar to the work I did restoring Torah scrolls from Prague. The Torah scrolls and the violins have this in common—they are brought back to life when they are repaired and used in synagogues around the world.”

As the program at the Vilar developed, it included some Yiddish and Hebrew music but mostly secular compositions, so Rabbi Newman had yet another idea. What if Avshi and the eight Violins of Hope stayed in Vail through the week for Shabbat, and at the service, a violin would be played to replace the prayers that are usually sung? This, Rabbi Newman believed, would be a way the violins “truly come to life—by playing liturgical music.”

“By bringing the violins to the Vilar, we are making this a bigger program, and that exposure is proper,” Rabbi Newman says. “But to bring it back to the shul is incredible. If you go to a Holocaust Museum, you might see a violin in a glass display case, but when you take it out and hear it again, everything changes. Now it is alive, and we have brought the violin owner or maker who may have been killed in the Holocaust back through the violin.”

The Donors

Rabbi Newman praises the congregation of B’nai Vail for their strong support of programs like Violins of Hope.

“Most people would say what I want to do is impossible,” he says. “If you don’t have backers who believe in what you are doing, it would not be possible.”

Bernie and Helene Grablowsky willingly stepped up to make the Violins of Hope visit to Vail a reality.

“Rabbi Newman is the pied piper of Judaism here,” says Helene, with a laugh. “Wherever he goes, people come. We decided to support this program because it’s our desire to bring pleasure to the many people who have become our friends in Vail.”

The Grablowskys have been coming to Vail for 15 years, and they have been active at B’nai Vail since 2018 where they have met “phenomenal people” and experienced “interesting and unique services.”

Bernie was particularly interested in the Violins of Hope program because he lost 20 family members in the Holocaust in what was then Russia and is today Belarus and Lithuania.

“I was surprised and pleased that so many non-Jews bought tickets,” he says. “I think that for non-Jews, the Holocaust just goes over their heads because they have not lost family. When we agreed to this, we thought maybe we would have the program at B’nai Vail and 150 people would show up. Now we are completely sold out at Vilar!”

Both Helene and Bernie agree on why they did not hesitate when Rabbi Newman asked for their help. “We just made the decision to support this because we feel good about B’nai Vail,” they say. “We don’t care about being recognized. It’s our pleasure that we can do this at this time in our lives and watch the enjoyment this program brings to Vail Valley.”

The Partner

As Program Manager at Vail Symposium, Megan Bonta oversees 40 events a year on a wide range of topics. But when Rabbi Newman came to her with a proposal to partner on this presentation, she saw it as “an amazing opportunity to highlight the Violins of Hope and work with B’nai Vail.”

“I’m excited we could have this event and bring the stories of these violins to a wider audience,” Bonta says. “Being able to touch the violins and hear their voices and their stories is a visceral experience. It just gives you goosebumps.”

Bonta says the educational mission of Violins of Hope aligns with Vail Symposium’s focus on education.

“We have done other history programs and other programs with B’nai Vail, and this one is really special to us, particularly because it tells amazing stories of resilience,” she says. “To many young children, World War II seems distant. This is a way to connect to that time through the journeys these instruments have taken.”

Bonta booked Violins of Hope into the Vilar, a larger venue than she usually uses. It sold out all 550 seats and an additional 115 people watched via livestream.

“We have a great partnership with Bnai Vail,” she says. “And Rabbi Newman does a great job getting the word out.”

Ask Bonta what success looks like for this event, and she has a clear vision. “Success is when people come away and say, ‘Wow, I thought of something I had not thought about before. Those hours were well-spent.’ That is what I hope for.”

The performers

The music at the Vail performance ranged from Bach’s Violin Concerto in D Minor for Two Violins to a traditional Yiddish melody and an Appalachian Waltz. The two violinists who performed were as different in their backgrounds as the music they played.

Sevil Weinstein, the wife of Avshi Weinstein, is considered to be one of the leading Turkish violinists of her generation. Raised in Bulgaria, she completed her violin studies at Istanbul State Conservatory, where she is now a professor. She has performed in Europe and the United States, but playing the Violins of Hope is more than just another performance.

“The people who owned the violins were playing to survive,” she says. “In this difficult world we are living in today, we must play the instruments in a way to remember their history, so it never happens again.”

Sevil performed in Paris on Violette’s violin just hours after it had been given to Violins of Hope.

“Seeing her children crying while I played the violin was a special moment,” she says. “It reminded me that these instruments provide a unique connection between humans and our history.”

The second violinist, Coleen Dieker, is an engaging, multi-talented performer who has built a following through relationships around the country developed over the past 15 years—with corporate clients, Jewish communities, festival communities, and with people who just love her playing —whether it is traditional, classical, jazz, rock or klezmer. She is a sponsored artist in residence at B’nai Vail. She was in Vail last winter snowboarding when Rabbi Newman first asked her about performing on the Violins of Hope.

“I immediately had chills, thinking about the violins and where they had been and who had played them,” she says. “Joel made that a reality.”

Dieker calls this opportunity a “huge honor,” particularly because she is a “Jew by choice.”

She grew up Roman Catholic and discovered Judaism when she was hired to play at a synagogue. Recently, at the age of 36, she became a bat mitzvah.

“Now more than ever, with antisemitism on the rise, it’s important to keep the story of the violins alive so that people see us and hear us,” she says. “There are not that many Jews in the world. These violins are carrying on a legacy, telling a story, honoring millions of people who were murdered.”