The USC Shoah Foundation, the organization dedicated to increasing knowledge and understanding of the Holocaust and other atrocities, has named Melinda Goldrich as Chair of its Board of Councilors. We recently sat down with Goldrich, a long-time Aspen resident, to talk about how this new role is very personal for her and what she sees as the future of Holocaust education and remembrance.

Were you eager to assume this new role as Chair of the Board of Councilors at the USC Shoah Foundation?

Actually, it took a bit of persuading. My first reaction was “Why me?” when so many other people seemed more qualified. But as I thought about it, I realized that I have become increasingly involved in preserving the memories of survivors and concerned about how today’s world is mimicking the past, particularly as it reflects antisemitism.

Actually, it took a bit of persuading. My first reaction was “Why me?” when so many other people seemed more qualified. But as I thought about it, I realized that I have become increasingly involved in preserving the memories of survivors and concerned about how today’s world is mimicking the past, particularly as it reflects antisemitism.

I took on the position on July 1, but before that, I had been shadowing Joel Citron, the Board Chair since 2022. I am following in his footsteps, knowing that I have a lot to learn about the Foundation’s relationship with USC and Steven Spielberg, the founder of the organization, and the Holocaust education community in general.

In what ways is this new role deeply personal for you?

It solidifies my father’s legacy which is more important to me as I grow older. It helps me find purpose and connection to what is happening in the world today. Finally, it helps create Jewish continuity which is a significant value to me.

For people who might not know, can you give a brief history of the USC Shoah Foundation?

It was founded by Steven Spielberg 32 years ago as a grassroots program after he directed and produced the film “Schindler’s List.” Spielberg believed that all Holocaust survivors deserve to have their stories told and memorialized. The project began by having other Holocaust survivors go into the homes of survivors and interview them and their family members with the theory that people would open up to other people who have a relatable experience.

Spielberg started with a large survivor population in Los Angeles where he lived. The project was housed on the backlot of his studio until it outgrew the space. In January of 2006, the University of Southern California (USC) took over the operations and archives.

When did you first encounter the USC Shoah Foundation?

It was when my father was interviewed in my sister’s home in 1996. I flew there to be with them for the interview. I remember being excited to hear my father’s story told in a narrative with an interviewer asking specific questions. It was a long interview. I don’t think he would have ever sat still so long telling his story outside of this formal request from the Shoah Foundation.

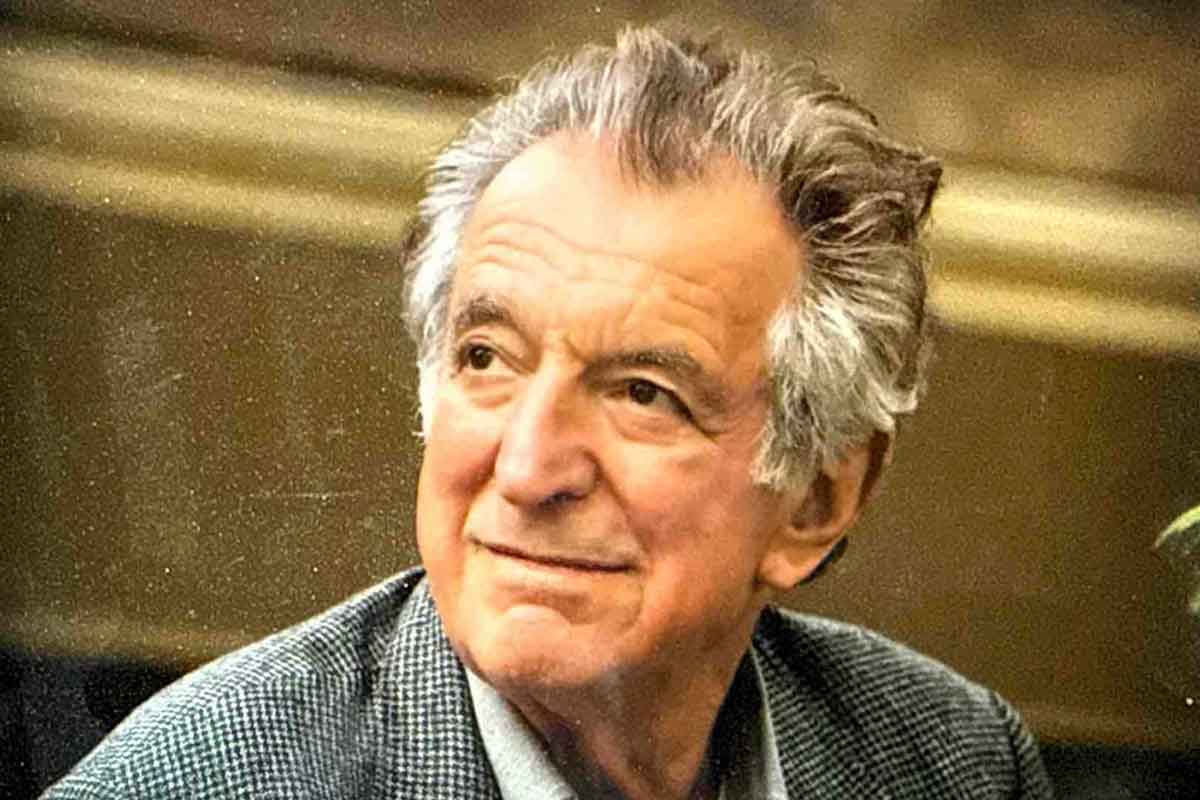

What was your father’s story of survival?

He was born in 1927 in what was then called the Galicia region of Poland, the middle child of three, in a town that was primarily Jewish. His father was a businessman, and he understood what was happening in the world. He was not the type to wait for some kind of divine intervention. He sent my father and my father’s younger brother away with Christian educators who were smuggling Jewish children out of the country with the thought that the rest of the family would follow them. He told my father that he should stay with his younger brother, no matter what happened. The family sent them with money and valuables sewn into their clothes.

Along with about 40 other children, they rode a train to Hungary. Every day, my father would go to the office of the Palestinian Authority—Israel’s government at that point in time—looking for passage to Israel. In 1942, he was successful, and he and his brother left for Israel. My father was 15 his brother was 13 years old. They never saw their family again.

How did he make his way to the United States?

He continued his education in Israel and served in the Haganah. His brother served in the Air Force and then worked for El Al Airlines. My father came to the U.S. in the 1950s and originally lived in Boston. But he didn’t like the cold, and he heard the climate in Los Angeles was more like Israel, so he took a bus across the country. In Los Angeles, he was taken under the wing of other Jews in the community, and he became a very successful real estate developer in Southern California and a pillar of the Los Angeles and Southern California Jewish Community.

Like so many others, your father’s story of survival followed by extraordinary success is remarkable.

I often think about Holocaust survivors and wonder whether they survived because of something in their nature or because of circumstances that taught them to be resilient. I always thought it was the circumstances that made my father who he was, but I have a cousin who says that it was in my father’s character. I think it can be a combination of both.

Was it your father’s story that led you to be interested in Holocaust education?

If someone had told a younger version of myself that I would spend a great part of my time in the world of Holocaust education and leadership, I would have said they were crazy. It has surprised me that I have taken this on because my father’s experience was a negative for me. As a child, I was forced into a constant reflection on my dad’s past. He would cross-reference my childhood with his. I grew up in Beverly Hills, so there were not many similarities, and I didn’t understand the comparison.

We all have experienced those “When I was your age” comments from our elders, but my dad’s story was an extreme version of that. I couldn’t help that my life was nothing like his childhood, and I became resentful.

Something must have changed for you because you have chosen to do this important Holocaust work now.

It was not a sudden epiphany. I think I matured based on my personal travels and the opportunities afforded to me. I became more open to understanding why the Holocaust was important to my father and the Survivor community at large. I realized that this population would eventually die off. Gradually, I began to see that it was my responsibility for the life I was privileged to lead to continue my dad’s legacy and the memories of others.

At what point did you reconnect with the USC Shoah Foundation?

In 2015, I was invited to attend the 70th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz-Birkenau. At that event, representatives of the Shoah Foundation absorbed me into their group. I felt like the board and staff were like-minded people, and I was drawn to their mission.

They shared my views that the testimony of survivors should be preserved in perpetuity and shared with the world, especially as we get farther away from the Holocaust. Unfortunately, history DOES repeat itself. I didn’t expect to what extent it could be repeating itself in today’s world. I believe that without the preservation of these testimonies, we would live with Holocaust minimalization or denial. The only way to respect and honor the people who lived through the Holocaust or perished is to record and share their stories. In the Shoah Foundation, I found a community of people who believe that as well.

After you reconnected, how did you start to become more involved?

I didn’t jump in—I started by dipping my toe in the water. Over time, I developed an understanding of how Holocaust education was dependent on the direction technology would take. The technology of the future will ensure that stories are not lost or forgotten. In 2017, I made my first significant gift, establishing the Jona Goldrich Center for Digital Storytelling, honoring my father.

Do you have specific goals for your three-year term as chair?

I have tremendous respect for the staff at the USC Shoah Foundation, many of whom are not Jewish. When I ask them why they would choose Holocaust studies as their career when it is not even their history, they say that they are drawn to that era because history has a way of repeating itself.

My goal is to find the next generation of board members who can provide lay leadership for this excellent staff.

We also want to capture testimonies that we do not yet have, and that may mean absorbing collections from other institutions around the world.

We want to make sure that the 55,000-plus testimonies that we have are freely accessible and readily available to everyone, so we need to find financial endowments to move us into the next iteration of technology because we know it will change again. One of the most expensive and difficult tasks is indexing all the testimonies so they are readily searchable. It’s possible that could become a positive use of AI.

You have made several references to your concern for the state of the world today. What specifically keeps you up at night?

I think we need to be aware of antisemitism in countries around the globe today to prevent it from escalating the way it did in the 1930s. The many forms of communication we have today allow more outreach by antisemitic people and groups. That is why I worry about the future and believe that the work of the USC Shoah Foundation is so important. I want to ensure that future generations do not experience what my father’s generation experienced.